Terry: [was talking privately over dinner with Tess until Terry finally shows up] I know everything that’s happening in my hotels.

Danny: [sarcastically] So I should put the towels back?

Terry: [while rubbing Tess’s hands] No, the towels you can keep.

-From the film Ocean’s Eleven

One of the great things about writing, as with communicating with dogs and babies, is that the reader can’t talk back. This notice is a perfect example.

In sales, there’s a scummy tactic called the “assumptive close.” This is when the car salesman starts writing up the order, and asking questions about thing like color and options, before you’ve actually agreed to buy the car. The often-effective method here is that once the buyer gets used to making decisions and saying “yes” they’ll just simply keep doing it, and thus buy the car if the salesperson acts like they’ve already decided to. Otherwise, the buyer has to stop him, and who wants to do that?

Writing works the same way. Every piece of written work has a bunch of assumptions baked into it about the world, about the topic, the reader and so on. Some of these are obvious, some are not. But they’re always there. For instance, I remember reading an article in Vanity Fair once about someone going somewhere in Los Angeles. It included the phrase “in someone’s X5”.

An “X5” is a BMW X5. This is a luxury SUV, with a base sticker price of around $60,000. I’m going to guess that when you finish adding in all the fun extras BMW offers, you’re in the price range of $80,000. In other words, this is a very expensive, fancy, high-end car that costs what, in some places, a house costs. But the inclusion of the word “someone’s” carries with it a whole load of assumptions – that everyone has one, that owning one is not a big deal, and that driving around in something like this is so commonplace that you don’t even have to know whose it is. It’s just someone’s. And everyone, of course, is assumed to know what an X5 is, and not make the gauche and embarrassing error of thinking it’s say, shampoo or dog food or a nutritional supplement.

See how this works? Very effective marketing writing includes assumptions that reinforce what the writer wants the reader to believe, and these operate without ever being explicit. When a law firm capitalizes the word “Firm” in reference to itself, well, of course it makes sense, given the prestige and might of the firm, the make it a proper noun. You know, like the Catholic Church, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, the White House and so on.

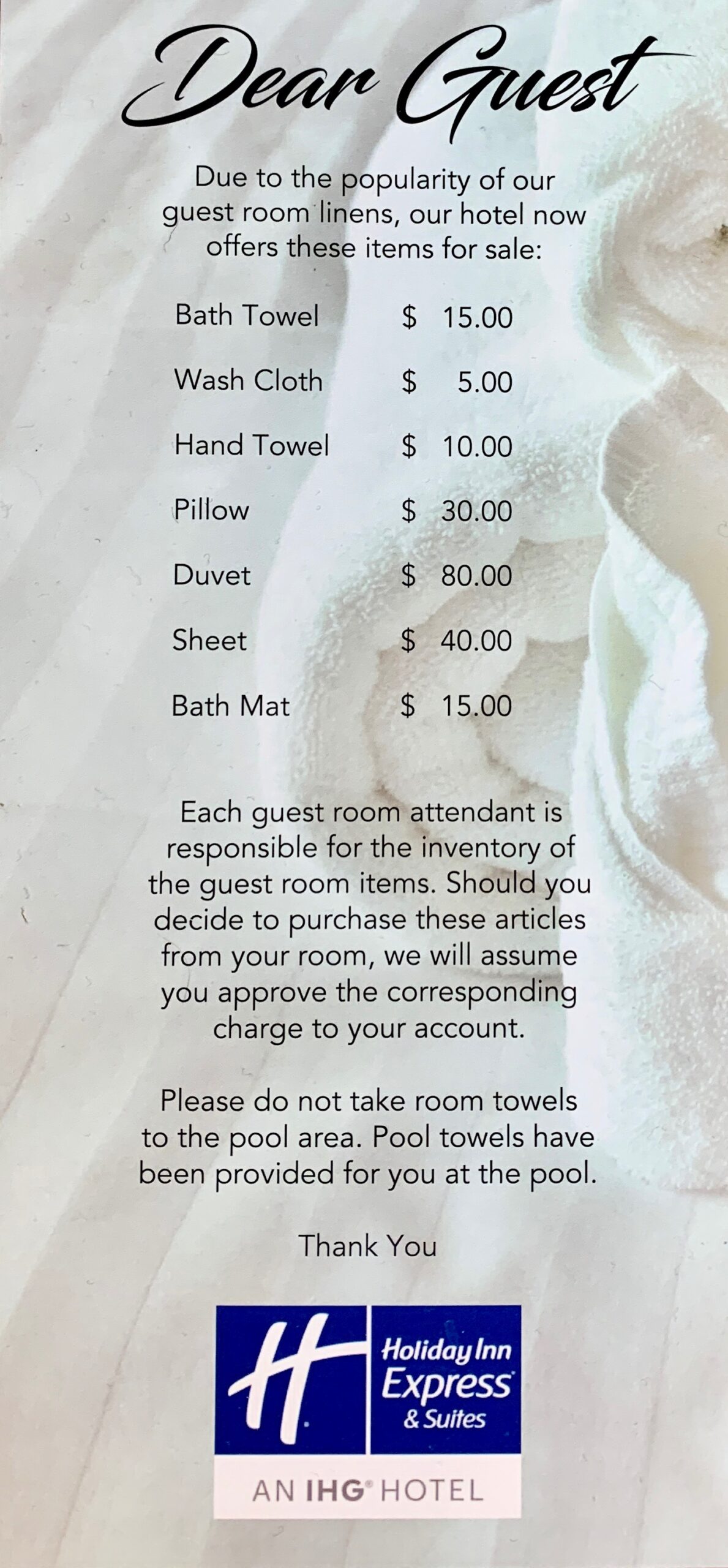

I thought of this because of this fantastic little notice that was in a hotel room I recently occupied. The reality at work here is that guests were pilfering things like towels and duvets and quite reasonably, the hotel was going to start billing them for it. However, instead of saying so, the hotel chain instead presented this not as “theft” but as “purchase.” If you steal a towel, they’re going to charge you for it, but by making the written assumption that it’s a purchase rather than a theft you got caught making, it seems legitimate, friendlier, more hospitable. “Oh, you like our stuff so much you want to own it? Of course you do! Who wouldn’t? We’re delighted to sell it to you.”

Marketers and politicians do this all the time. “Right to life” actually means “Making abortion illegal”. If you have a problem with increasing the tuition at a public university, you’re anti-education. An ad for mozzarella cheese shows a delicious-looking slice of pizza, with the headline “Eat in peace. For once.” Assumption: you have such a busy, on-the-go, exciting life that you really need your dining companions to be silenced by pizza. That’s quite an assumption for a bag of grated cheese. But that’s how it works.

In writing, what isn’t said is often at least as important as what is. Or, to quote noted philosopher Sammy Hagar, frontman (for a while) of Van Halen, “What is understood doesn’t need to be discussed.”

Now, put those towels back. Now. I mean it. Those things aren’t free.